Turning Content into Knowledge - Leveraging FOAMed for Lifelong Learning in Medicine

A personal knowledge management system is key for physicians to stay current, make connections, and create new knowledge that can shape the future. With the right tools and approach, physicians can learn to think differently and become creators of knowledge that can have an impact.

Last week I gave a talk at the annual winter Oregon ACEP conference, discussing how to design your personal knowledge management system as a physician. Below is the script I drafted for the talk.

Introduction

Joseph Gutenberg: “To help men and women be literate, to give them knowledge, to make books so cheap even a peasant might afford them: that is my hope, yes”.

…

Monk: “The Word needs to be interpreted by priests, not spread around like dung.”

Around 1450, a man named Joseph Gutenberg was working on a technology called the printing press. Before that, most knowledge was shared through oral storytelling and speaking. Writing down knowledge was difficult and was usually only done for religious texts that were copied by hand. The printing press allowed for quick and accurate reproduction of text, making it possible to copy information that was not previously considered important enough.

It allowed information to be accessible and no longer regulated by gatekeepers. It created fear among those in power that the information would become dilute. Ultimately it ushered in a new era of enlightenment and jump-started the Industrial Revolution.

It is this same spirit of decentralized knowledge that is driving the future of medical education. With the rise of social media and the internet, much of the knowledge shared in the medical community is now disseminated through online resources like Twitter, blogs, podcasts, and newsletters. While primary literature is still the foundation on that evidence-based medicine is built, medical education will continue to become more decentralized, much in the same way that the internet has changed other industries like traditional media with social media, finance with cryptocurrency, and art with NFTs, to name a few. As this landscape continues to develop and mature, we all need to design our own systems to evaluate and integrate the information that is being shared.

My goal today is to share my perspective on how to approach the process of turning content into knowledge by designing your own personal knowledge management system. While having tools to assess the quality of content is important, the more pressing need for any one person is to develop the skills and system for digesting the material you consume, to compare it against the mental models you've built from prior experience and knowledge, and to understand its concepts and lessons more fully in context.

The question to ask yourself anytime you read, watch, or listen to something is: “What is the job I need this information to do for me?” There is an adage in design that people don't want a quarter-inch drill bit, they want a quarter-inch hole. The drill and bit is the vehicle to get to where they want to go. When you consider how you interact with medical education content, are you clear on the job you are wanting that information to do for you? Something you use on shift as a just-in-time resource will differ substantially from something you use to build or evolve your conceptualization and practice of emergency medicine. You need the clinical reference to be as accurate as possible, you don’t know the answer and you need the best answer as soon as possible. The material you use to evolve your thinking needs to only push you to think about something differently, then it’s on you to digest it and decide where on the spectrum of truth it lands.

I was tasked with sharing how to evaluate the quality of FOAMed and how to use it clinically.

Over the next 20 minutes, I will discuss metrics used in traditional scholarly publishing such as the h-index, journal impact factor, and other similar attempts to objectively assess FOAMed resources. Then, we will explore why consuming a broad and diverse range of information is important, and how to design a system for extracting what is useful and connecting ideas to form mental models of the information you take in. I will share some tools that I have found to be useful, and end with some thoughts on the value of creating and where the technology may take medical education in the near future.

Metrics of Effect

Two common metrics used in trying to objectively assess the effect of scholarship are the journal impact factor and H-index.

The h-index is a metric used to measure the impact of an individual's research output. It is calculated by counting the number of times a researcher’s papers have been cited, then comparing it to the number of papers they have published. The journal impact factor is a measure of the impact of a journal, based on the number of citations its articles receive. It is calculated by taking the number of citations from a journal in a given year and dividing it by the total number of citable articles published in the previous two years. Both metrics are used to assess the quality and reach of research and are used to compare the impact of different journals and researchers within the same field.

Over the past 10 years a group of emergency medicine educators affiliated with the popular website Academic Life in Emergency Medicine, or ALiEM.com have sought to create objective measures of quality for FOAMed sources. They first developed the METRIQ-8 criteria which use an 8-point criterion to assess the quality of an individual piece of content. The criteria are based on the type of evidence the content is based on (e.g. randomized controlled trials, case reports, etc.), the content’s relevance to medical education, its authors and sources, the content’s accuracy and clarity, and other factors.

This evolved into their creation of the Social Media Index, which is an amalgamation of a website's Alexa score (a metric of overall website traffic), Twitter, and Facebook followers. In essence, it's a metric assessing the overall followership of a website and its author(s), with the thinking that higher quality content will drive more readers and followers. In a paper from 2020, they showed that the Social Media Index had a generally good correlation of quality when compared to expert gestalt and their METRIQ-8 score, meaning it serves as a reasonable tool for assessing the general quality of a FOAMed source.

ALiEM has since created the ALiEM AIR series which seeks to collect the highest quality and most pertinent content based on these metrics and additional expert evaluation. There are actually numerous websites that have collated high-quality content online, including many which had created curricula for trainees and other learners in emergency medicine to use to supplement traditional didactics and teaching.

High-quality, free, content online exists. The question of ‘how do we assess quality?’ is less interesting than; ‘what is my system for integrating what I read and consume into my clinic practice?’. Think of the last time you needed to look something up on shift; a medication dose, a differential diagnosis, or to get some help with determining a patient’s disposition. What resource did you use? Like most of us, you probably used an established, trusted source like uptodate, wikem, or guidelines from a professional society. The time you spend outside of your shifts, reading, watching, and otherwise deepening your understanding of a disease or patient presentation is how you develop the foundation of your practice rests. This process is what will continue to shape your clinical practice.

Personal Knowledge Management

In the mid-20th century, a German sociologist named Niklas Luhmann was a young civil servant and Ph.D. student interested in legal systems theory. While studying, he would take notes on pieces of paper and stick them inside the books. As the note count grew, the books would become too thick and damage the book bindings. He started putting them in folders instead but then couldn’t find notes when he needed to reference them. So he created a file system in which notes were organized around a particular idea or concept and referenced one another.

In his words; “I started the index card file for the simple reason that I have a poor memory…it was obvious to me that I would have to plan for a lifetime, not for a book”. He realized early on that the information he consumed would build around the core ideas that formed his thinking. Imagine how much easier writing is when you’ve already done the work of clarifying your thinking and just need to piece it together. This process was what led to him being among the most productive academics of the 20th century, having published more than 50 books and over 500 journal articles!

What Luhmann created was a network of ideas organically built from the material he consumed. When reading a text or article, he would be reading with an eye toward comparing and contrasting material with the information he had already saved. When he captured a new snippet, he would recall notes already in his file. In this way, he could take ideas from seemingly disparate domains and begin to string together a mental model of the overarching concept.

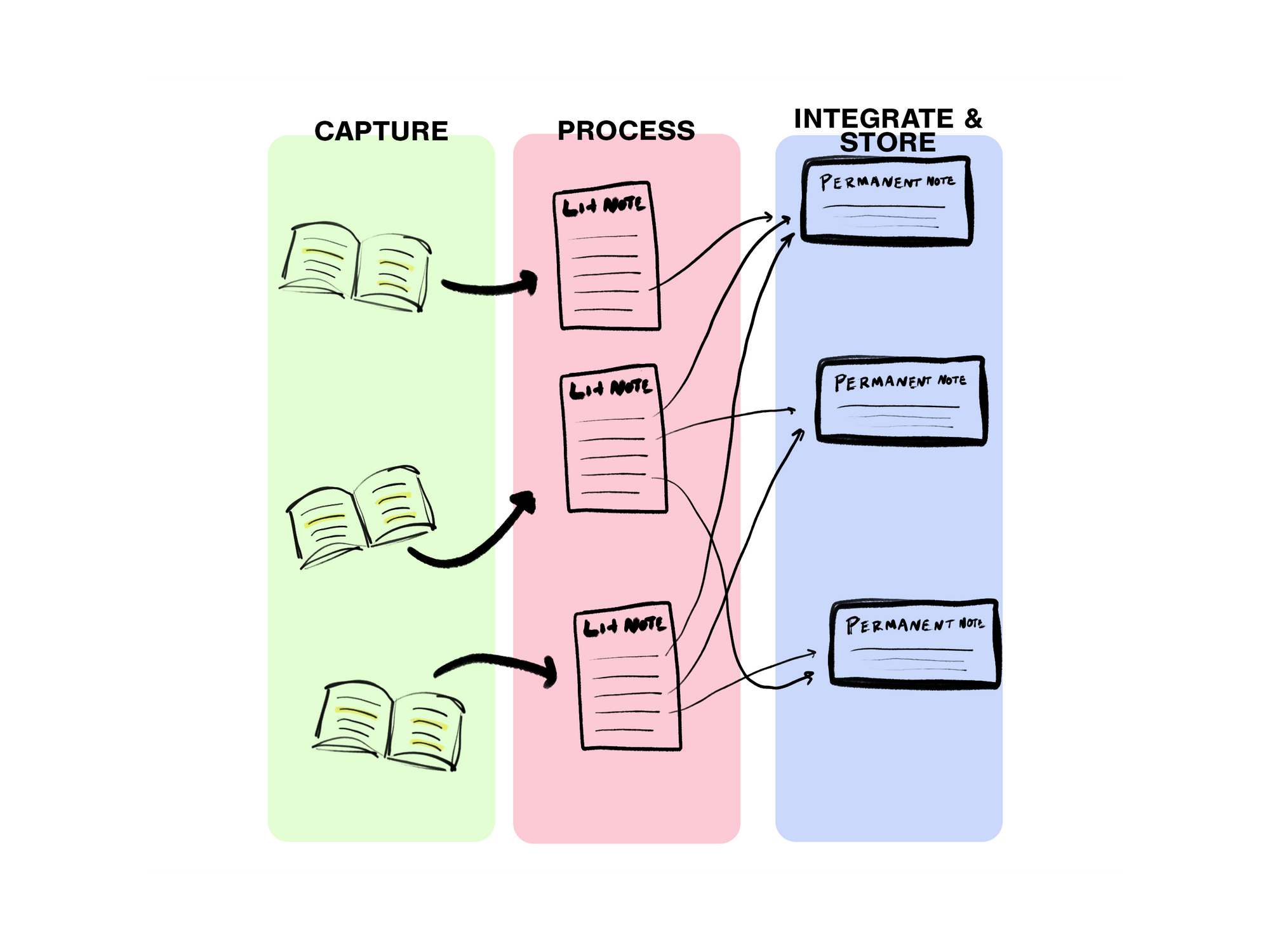

The process looks like this: take notes while reading, listening, or watching material, summarize those notes into your own words to ensure understanding, and link the concept with thoughts, ideas, and concepts already in the system. As more notes coalesce around a concept or idea, they form what Luhmann called a “permanent note”; these form the core of the system and serve as a cognitive foundation. As the foundational components become apparent, create an “entry point” into the file using an index of fundamental ideas that you reference when placing new notes. The system is not structured around an index though, it’s built through linking notes and ideas over time.

He called this system the zettlekasten, or “slip-box”.

As you distill information into your own words, you test your understanding of the concepts. By comparing the material with other inputs into the system, you give it context and deepen its meaning. The material is no longer just information, but knowledge. It becomes adaptable and in understanding something more fully, you can apply it to new contexts or situations - which really is the meaning of mastery.

The problem we all face is that no one, in the decade or more we all spend in school and training, ever teaches us how to take notes. It’s too often taken for granted. We all stumble into some process of consuming and ingesting material, but has anyone ever shown you how to take what you read and use it to form new ideas? By taking concepts from Luhmann, we can each build our own slip-box to change our relationship with the information we take in. If your goal is to deepen your understanding of something or to form a foundation to build on through your career, you need a way of capturing and processing that information to form knowledge.

Practice and Learning

The best research in cognitive psychology has shown that learning occurs most effectively when something is practiced in diverse contexts; it’s a concept called varied practice. If you want to learn the pathophysiology of sepsis, you need to encounter its concepts from multiple contexts to begin integrating the material into the mental models that form your understanding of sepsis. Meaning, you need to understand how microcirculatory changes lead to vasodilation which drives low cardiac output, how to assess fluid responsiveness, measure capillary refill, etc. You might bridge your understanding through analogies from your understanding of anaphylaxis or use that in contrast for thinking through causes of elevated serum lactate other than infectious causes. If you don’t read broadly and instead focus on single papers or professional guidelines, you might begin to conceptualize sepsis purely around data points like a serum lactate level, white blood cell count, or a mandated fluid bolus.

The opposite of varied practice is called blocked practice; practicing the same concept or skill repeatedly in the same context. Think of the last time you used flashcards to prepare for an exam or practiced a procedural skill with the same equipment or setup, that’s blocked practice. You become an expert in that single context, though competency drops when the same concepts are encountered in new situations. The knowledge you’ve built is less flexible. The idea of deliberate practice is an enticing one. With the right feedback and approach, you can master anything with enough time, it says. While that’s partially true, the challenges we face in the emergency department don’t fit neatly into one box and instead require adaptability which isn’t built through boxed practice.

Intuitively, this makes sense to us. We all can understand how a diversity of input leads to a more comprehensive understanding of something. It becomes a bit more difficult to understand how to design this into your life once you’re done with med school and residency, though. It becomes your responsibility for designing a system in which you interleave information to create a “latticework of mental models”, as Charlie Munger put it in 1994.

We know this can’t come purely from reading hot-off-the-press primary medical literature though. Part of the problem is that papers which combine knowledge in new ways are less likely to be published in more prestigious journals. They accumulate citations more slowly though become the foundation for thinking. Papers which are immediately popular are more likely to combine knowledge in traditional ways. It takes time for people to catch up to new ideas or ways of thinking. What you read in primary literature is more likely to be incremental in evolving your thought or understanding of an idea.

To think differently, you need to weave sources of information together to form new connections. It means reading not only primary emergency medicine literature but also reading literature across specialties. To evolve your understanding and mastery though it can’t stop there, you need to read medical content outside of the traditional publication process and integrate it into the information system you’ve created, to develop the mental models needed to drive your clinical practice.

Best Practice

Regardless of the tools you use, you need a way to capture inputs in a consistent and unified way. How many times have you come across something, wrote it on a random sticky note or napkin, and then two months later remembered vaguely what you wrote down but couldn’t find where that note went?

Your personal knowledge management system is made of three components

- Capture

- Processing

- Storage

While Luhmann built his system in the analog world, the benefits of a digital system are just too great at this point to not use digital tools. A guy named Tiago Forte wrote a book entitled Building a Second Brain and discusses a process of storing digital notes to make them useful in building a personal knowledge management system. He breaks down the pros and cons of multiple digital tools and I’ll direct you there if you’re interested.

I’ll give you a broad overview of my general process for digital note-taking and share a few of the tools I think are close to essential.

Capture

This is more flexible and really depends on how you find yourself consuming information and having ideas. If you primarily read printed copies of articles, books, or other media, a small notebook might be best. If everything you consume is digital, then it’s probably best to have a digital tool that best captures those digital inputs. Regardless of how you get it there, information needs to be routed to as simple an inbox as possible.

The tool I think does this the best is called Readwise. It started as a service that automatically imported kindle highlights and notes to common digital notes apps. Now it’s evolved into a read-it-later app that allows you to send nearly any type of media into your personal inbox where you can consume the information while sending your highlights and annotations to your notetaking app of choice for processing and integrating.

For example, I use Read to create a feed of primary medical literature. I can download articles directly and send them to the Readwise inbox where they’re stored alongside the FOAMed articles and Youtube videos I’ve saved to review. When I have time, I consume those pieces of content, creating the “fleeting notes” which then go into my note-taking app to be further digested and processed.

Processing

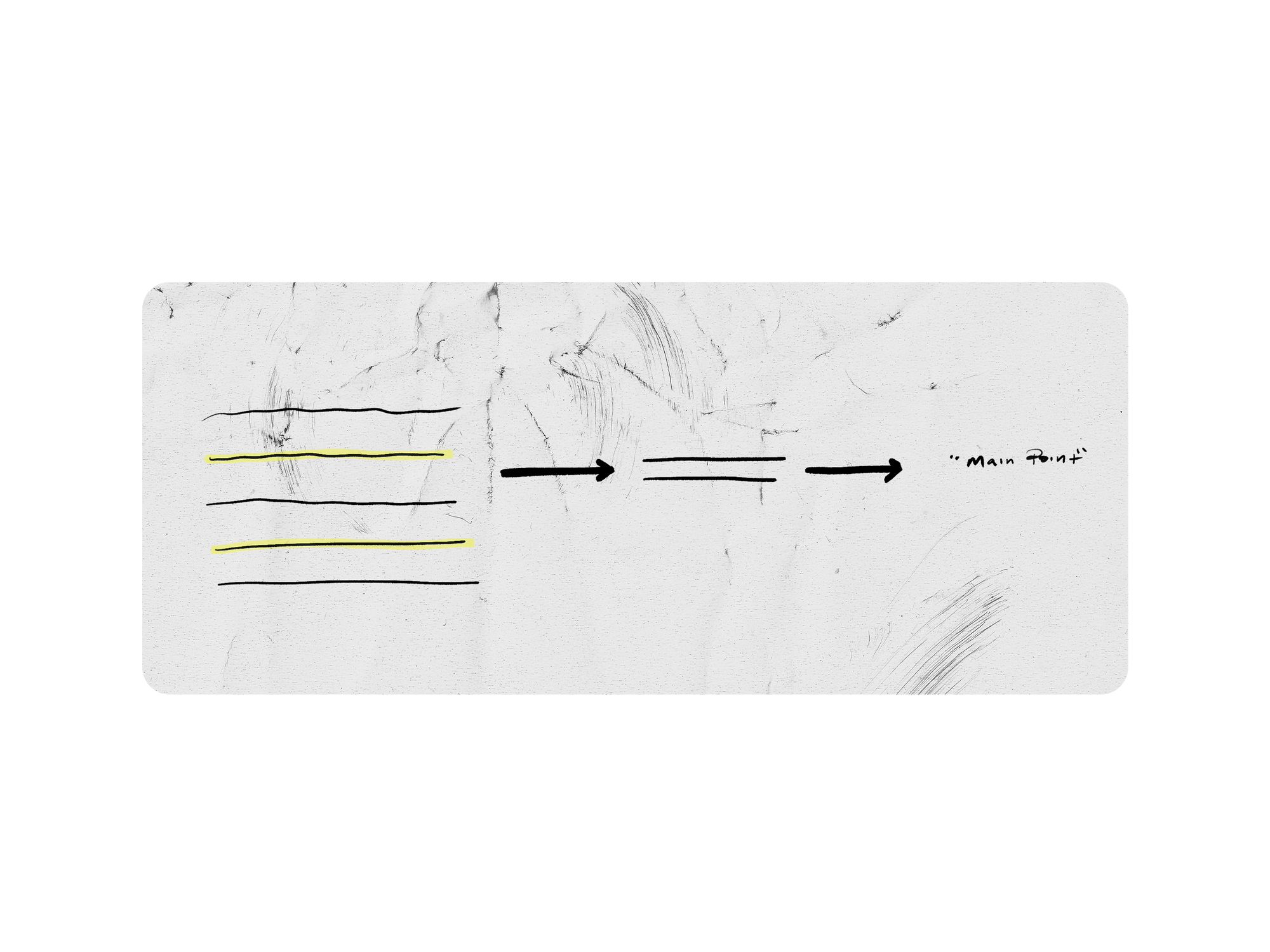

Given the demands on our time, processing information you consume by nature, can’t be systematic and comprehensive at all times. It’s just unrealistic. Instead, we need an ad hoc way of revisiting the ideas we’ve previously come across and found important. Tiago Forte, who I mentioned previously, calls this idea progressive summarization. Each time you encounter an idea, you add a layer of distillation. The more you come across that note, the more the idea is distilled. In this way, the most important ideas will by nature continue to surface and the deeper you will digest the idea into your own words and understanding.

The key is to consume information with an eye toward the future and the information you have already captured. As your system develops, an idea you come across when reading a paper will jog your memory about something you’ve already captured. By making a note about how it relates to what you’ve already encountered, you start the process of integrating it into an existing mental model. With your eye toward the future, you’re really trying to do your future self a favor by putting a stake into your thinking at that time. Don’t assume that some note you make today will make sense to yourself in three months. Give it context and a deeper understanding.

As you process the information you take in, integrating material and giving it meaning, you’re leveraging varied practice to understand principles in various contexts. As you summarize the content and provide layers of meaning, you’re using feedback loops to help assess your understanding of the concepts. If you struggle to write something into your own words, it’s a pretty clear sign that you don’t yet have the concept clear in your mind. The other side of that is if you work to summarize information and integrate it with existing knowledge and it doesn’t seem to fit, that might mean that particular information wasn’t accurate or maybe the edge of what’s known about an idea or concept.

Storage

All good information systems need a reliable way to store material for reference at a later time. The goal is to have access to the entirety of an article, book, video, etc. when referencing it later on. For example, you might write an article to publish in a journal and want to access all of the articles used as citations. Digital tools are obviously the most flexible, though they are sometimes at risk of transfer portability as you are dependent on companies like Google to not go bankrupt and immediately take away your access to what you’ve saved. For big companies, this is less of an issue, though, for newer apps, you might use, you should look into their export options if you ever need to migrate from them.

While you would ideally keep everything in one system, there are multiple tools available that do some parts of this better than others. The important thing is to first reflect on how you feel your brain works with information. Tiago Forte breaks down four different archetypes:

- The Architect: Plan in detail and engineer the perfect system

- The Gardener: Building from the ground up; allowing knowledge to grow organically

- The Librarian: Organize information for a specific purpose; hierarchy and clarity for your future self

- The Student: Information with an intended use

Once you have a better idea of how your brain thinks about storing information, you can use apps that are structured in a similar fashion. Tiago has a great article and video that go into more detail about different commonly used apps for each archetype on his website, fortelabs.com.

The Goal Should Be Creation

Ultimately, all of this work would be a bit pointless if you didn't do something with it. Whether it's providing better patient care, teaching, creating for others or just wanting to grow personally or professionally, the goal of this isn't just to accumulate information but to create knowledge. Not all of us are going to publish 500 journal articles in our career as Nikolas Luhmann did, but we could strive to publish one blog post a monthfthat researchers will soon be using generative technology to help draft journal articles. It means that you, the human, will only become that much more valuable, to combine information and build knowledge in a way computers will never be able to.

The power of creating knowledge lies in the ability to make connections between disparate pieces of information and use that to create something new. The tools of today are making it easier than ever to capture and store information, though it’s ultimately up to us to make the effort to understand and process that information. By taking the time to read broadly, distill information into our own words, and integrate it into our mental models, we can build a system of knowledge that can be used to create something new and valuable. The goal of creating a personal knowledge management system should be to empower us to make those connections and to create something that can be shared with others. With the right tools and approach, we can learn to think differently and become the creators of knowledge that can shape the future.