How to be anti-disciplinary [how to have ideas] \\ conclusion

Having ideas is the easy part. Having a system to actually carry them through is where you earn your keeps.

![How to be anti-disciplinary [how to have ideas] \\ conclusion](/content/images/size/w1200/2021/11/25205D27-54E2-4C1C-AF10-035648C96D7D.jpg)

I'm back after a few weeks' hiatus. I took some time to prepare for and take the first exam to become board certified in emergency medicine. Nothing like a 7-hour exam to have to commit your time and attention!

In the previous post I shared how anti-disciplinary, design and breadth are crucial in medicine. Here, I cover how to have ideas and actually act on them.

I think we're all taught how to be mostly average. It makes sense; the average is the place where we all feel most comfortable; not too far ahead of the pack and set up for a crash, not too far behind to feel less than others. Tests are graded on a curve. We strive for jobs with well-established track records to make sure we keep it all between the lines. We're not taught how to have and nurture wild ideas. We talk about "dream jobs" but not how to make them happen. "Do what you love" - just make sure you're also able to check the boxes of success along the way. The reality, I think, is that we have to find a way to harness those wild ideas and carve them into the things we do regularly. To make small changes that eventually lead you to where you want to go. You can design your life.

Some books I've come across the past few years have changed the way I've thought about this. I've mentioned them in previous posts; I'll make sure to do it again here. The first is Loonshots by Safi Bahcall. He's a physicist and technologist; the book teases apart the traits of people and teams who either break barriers and change the world or fall flat along the way. The second is The Practice by Seth Godin. I've referenced this book many times recently, and with good reason, I think. It has genuinely shifted my thinking when it comes to creating my work. It pushed me to think of my ideas as something to share and has been the impetus to go from having thoughts to creating for others.

Knowing your audience

The thesis of Loonshots is that teams and organizations follow three fundamental principles when it comes to innovation; phase separation, dynamic equilibrium, and mass effect. If you have any background in chemistry, these terms probably mean something to you. As ice melts, water molecules bounce around, wiggling between solid and liquid states. There is no state of "partially frozen molecules." Crucial in the phase change of water is the ability for any molecule to transition to one phase or another; there's a dynamic equilibrium. Once a molecule has shifted phases, it then may influence its neighbor to do the same. When enough molecules are heading in the same direction, the phase change occurs, and ice, water, or vapor forms. Bahcall uses this analogy to describe how ideas are had and nurtured by groups.

Phase separation

Like ice and water, organizations need to have a clear separation of phases. To be sustainable, an organization has to balance pipe-dreams with sure bets that will pay to keep the lights on. Recognizing where you stand between those two groups goes a long way to know how to communicate your ideas. Is what you do daily necessary to keep your organization or group above water? It might be a hard sell to wholly upend a company's accounting strategy.

Similarly, different organizations require varying degrees of certainty to move forward. Tech start-ups can go all-in on a big idea because they don't have a lot to lose. Huge organizations with thousands of employees have many competing interests that giant leaps of faith are difficult to sell. The "enterprise group" often vastly outnumbers the "loonshot group."

Dynamic equilibrium

Water molecules constantly bounce between phases states when nearing their freezing point, for example. Enterprise and loonshot groups must create a "seamless exchange of ideas" to help foster innovation while keeping an organization's best interest in mind.

Critical mass

It takes three people to start a trend. One to have an idea, one to follow, and a third to start the movement. Critical mass is the tipping point when enough water molecules transition phases, influencing all other molecules to do the same. To nurture big thinking, a certain amount of buy-in is needed to keep the ideas afloat. I think important in this are the essential questions all good designers ask; what are you improving, and who is it for? Being clear for yourself and communicating that clearly and often to others is the surest way to generate buy-in. To create critical mass, you have to learn how to make your problems important to others.

"The natural tendency of most companies is to constrain problems and restrict choices in favor of the obvious and the incremental. Though this tendency may be more efficient in the short run, in the long run, it tends to make an organization conservative, inflexible, and vulnerable to game-changing ideas from outside. Divergent thinking is the route, not the obstacle, to innovation." -Tim Brown, Change by Design

It's important to remember that change disrupts the way things have been done historically. When things change, people become upset, leading to resistance. You have to plan how you're going to respond to this. The buffer will be empathy, trying to put yourself in someone else's shoes and understand how another person is experiencing the change. This is what makes a design approach so helpful in innovating and problem-solving. Design, at its essence, is a process of striving to build empathy for how someone may use or experience a physical good, workflow, or process. Adopting a designer's mindset for your life unlocks a reproducible path to have, hold and nurture loonshots.

Good designers ask two questions throughout any project to ensure the context is well understood: "What are you trying to improve? Who are you trying to improve it for?" - Scott Berkun, Design Makes the World

Think like a designer

Divergence

Like all design problems, loonshots start from a collection of divergent ideas. Divergent thinking is an unfiltered stream of creativity - often a scary place for individuals and groups. We're taught to be practical; we lose the curiosity that drives the "what-ifs" children have perfected. "What if we lived in a world without cash"? "What if I documented every day with a 1-second clip for the next year"? "What if I wrote an unprompted email newsletter for my coworkers every Monday"? "What if I had to hand draw all the graphics for my next presentation"?

What typically limits us is the self-doubt and automatic criticism that starts to spill in after we begin to hold onto the what-ifs. As soon as we hear that voice, it drowns out our creative voice. "You're too old." "You're not good enough." "That's a waste of time." To have any good ideas, you have to have a lot of ideas, and if you start to criticize the thoughts you do have, there's no way you'll give yourself the freedom to keep going. Learn to compartmentalize divergent thinking by giving yourself (or group) the intentional space and time for having wild ideas. Since COVID started and we've been forced to work more remotely, there have been dozens of new digital tools to help facilitate this type of work among teams. Here's some I've enjoyed over the past few years:

- Miro is a great virtual whiteboard and is free for students and teachers.

- Milanote is beautiful and really nice to visually brainstorm.

- Figma, also free for students and teachers, is a popular design platform with a new collaboration and digital whiteboard platform called Figjam.

- Notion is a vast space that can glue it all together (also what I draft these posts in).

- Roam Research is a mental lab bench for connecting your thoughts to explore ideas and uncover nodes of thinking.

Regardless of the tool, find a process to create space physically and cognitively to let your mind take you to the edge of "what's possible." Save the judgment that comes next. Suppose you start to criticize ideas before you've exhausted the tank. In that case, you'll impede the creative machinery you need to eventually hit it out of the park.

Convergence

All good ideas have to eventually gain focus. I think one of the most challenging aspects of any creative pursuit is functioning within constraints. It's easier to write a long blog post than a short one. Including all of the features in an app is an easier decision than distilling them down to the most essential. Remember using Windows on the PC in the early 2000s?

Legendary designer Dieter Rams is well known for his list of "10 Principles for Good Design":

- Good design is innovative

- Good design makes a product useful

- Good design is aesthetic

- Good design makes a product understandable

- Good design is unobtrusive

- Good design is honest

- Good design is long-lasting

- Good design is thorough down to the last detail

- Good design is environmentally-friendly

- Good design is as little design as possible

To check these off, you have to be clear on the values of what you're designing for. What are you trying to improve? Who are you trying to improve it for? Once you have a collection of ideas that span what's possible, then start to apply a critical eye, filtering them through a lens that helps bring them back to "what" and "who." There may be other constraints you need to keep in mind at this point too. Cost, feasibility, time, technology. You aren't going to complete a randomized clinical trial during your month-long rotation in med school.

These are steps many of us take automatically, and it might seem silly to do so explicitly. Still, when applied systematically and reserved for use only after you've allowed your creativity to go to work, you might find yourself taking steps in a direction you might otherwise have ignored. I think we all naturally have a "convergence" mindset, so this step may feel more familiar. The issue is we typically move to this stage before we let ourselves have wild ideas in the first place. Here are a few tools I like to use when converging on a concept (there's an entire industry dedicated to this stuff, and it's often geared toward groups and organizations - just explore and find what works for you).

Pros & Cons

The classic tool to evaluate a decision or idea. A great place to start if you're not sure where to start - just make sure you don't take this step before you've spent time having ideas in the first place.

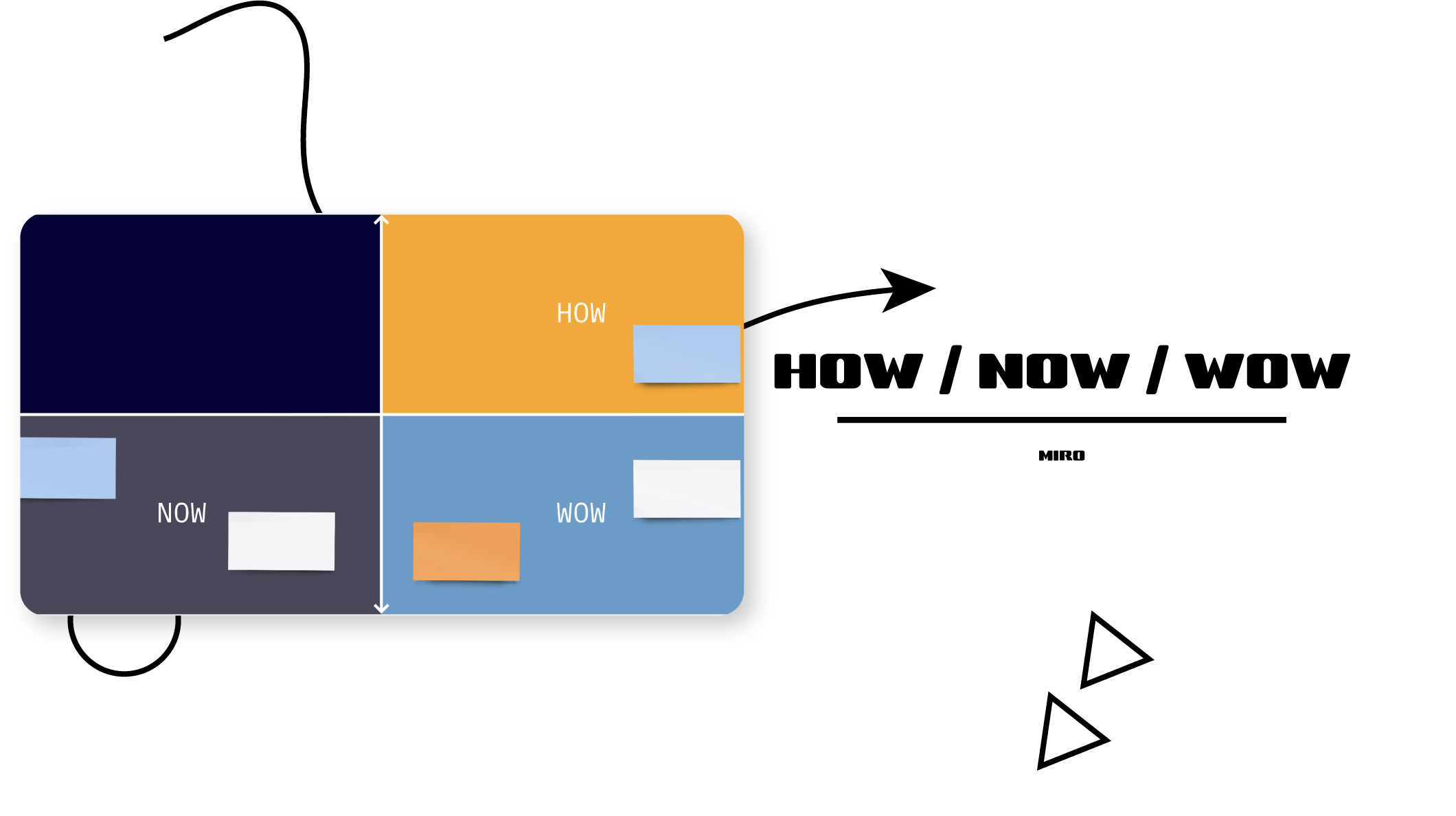

How / Wow / Now

A visual plot of how innovative and challenging something is likely to be. It's like an Eisenhower matrix and helps give some priority to your ideas. Change the criteria to match the constraints you're designing in. Think of "how" ideas as the future, "wow" ideas as next steps, and "now" ideas as incremental. Prioritize the next steps.

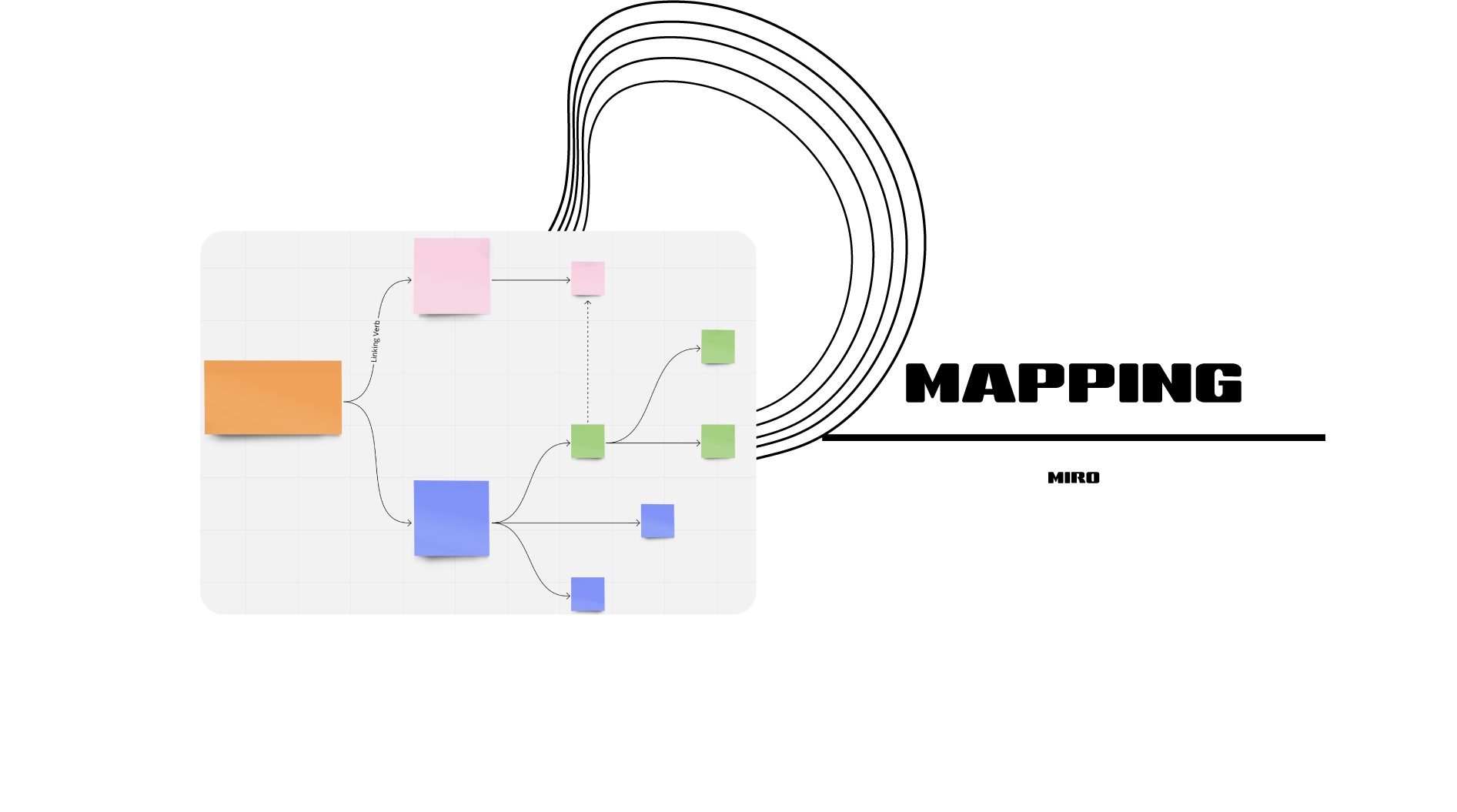

Concept Map

Like most people, I tend to think visually. I almost always create some sort of diagram to give shape to ideas when I have them. All of my blog posts start as a mind map. Use a concept map to understand your thoughts in space to better understand how your idea will interact and function in the "real world."

Again, there are college courses, textbooks, dozens of apps, and online software - entire industries - dedicated to creating tools for having and evaluating ideas. Look around, play with them and learn to apply them intentionally and systematically. The critical thing to remember is that, while it's essential to allow yourself to have ideas before you evaluate them, it's still not an entirely linear process. The act of converging on what you feel is the best idea may spark new ideas. It's an iterative process that may lead you to diverge and converge multiple times until you think you're heading where you need to go.

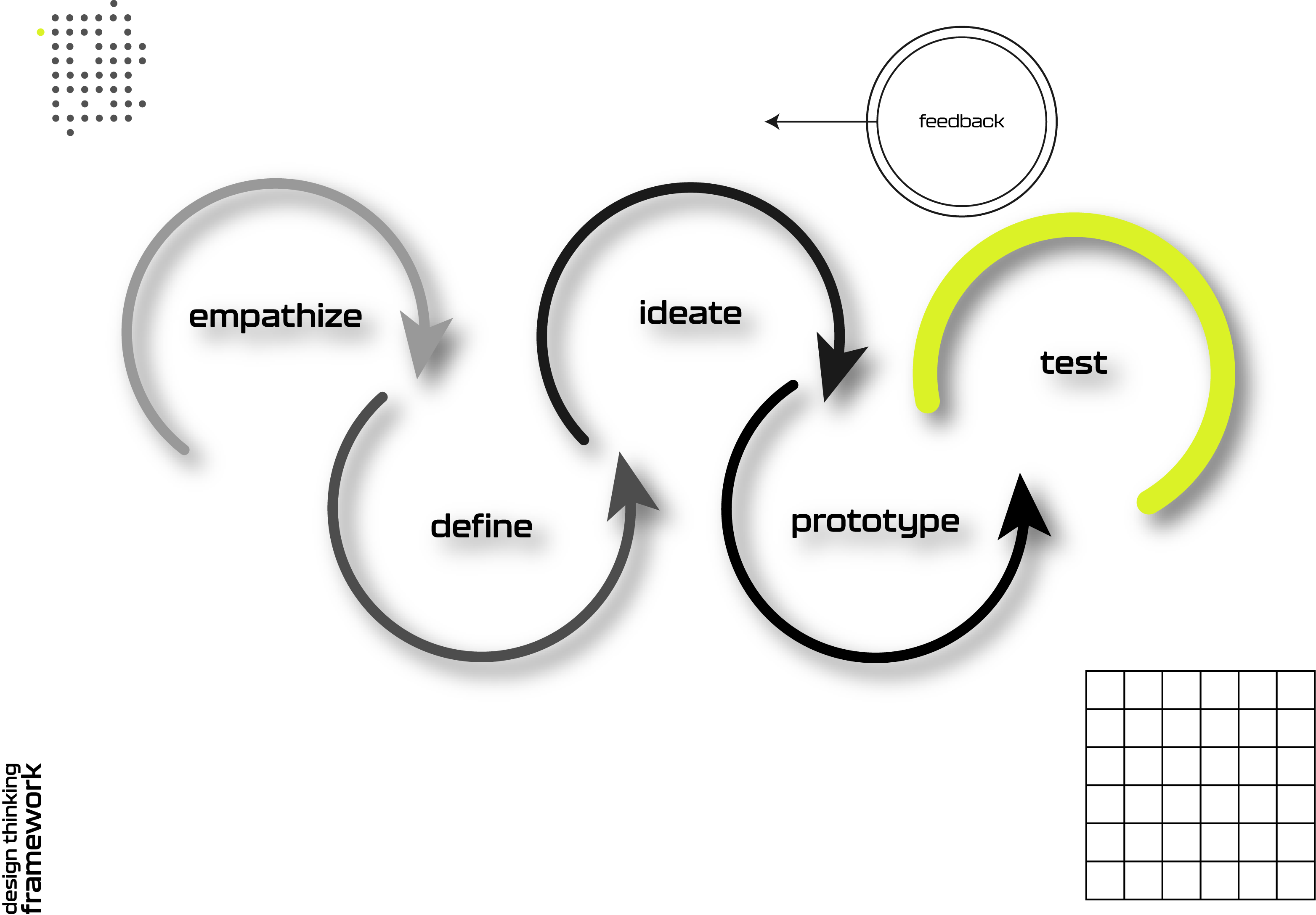

Prototype

When people hear the term prototype, they often think of expensive, hi-tech models of cars, computers, or props from sci-fi movies. I mean, and generally implied in the context of design, is the minimum needed to give a sense of tangibility to an idea. The fidelity of a prototype may likely improve as your idea is refined. Still, the quicker and rougher it is, the better, early on. In fact, you might start to create the first prototype immediately after writing down an idea during a brainstorming session. A prototype can spark new ideas. Maybe most importantly, a prototype allows an idea to be "tested" to find its pain points, failures, and improvement areas. The concept of "failing fast" helps you to figure out how to pivot before you've invested too much.

My favorite methods for prototyping:

Storyboarding:

An essential tool for storytelling. How will people interact with your product or workflow? How will you visually communicate your idea in a workshop, video, or presentation? My favorite tools to use for this are Milanote and Concepts.

Sketching:

I love the feel of sketching something out on paper - the tangible feel of analog media. Digital content is so much easier to store, organize and manipulate that I tend to gravitate to digital tools. Concepts is an app made with designers in mind. It's vector-based, meaning you can scale your drawings infinitely without pixelation and has an infinite canvas size. Using it with an Apple Pencil on an iPad Pro with a Paperlike screen protector feels like drawing on paper. I use it at each step to translate what's in my head into the world.

Playdough & Legos

I've recently rekindled my love for children's toys now that I have a kid. My soon-to-be 2-year-old daughter and I spend a lot of time making lego towers and playdough waffles. The thing that amazes me every time we play with them is how much I start to think about form, pattern, color, and other aspects of the creations we come up with. Having a physical object in your hand just seems to jumpstart your thinking differently than looking at digital things on a screen. I haven't brought this into my professional life yet, but I certainly will. I bring it up as a reminder that even the simplest tools can profoundly affect the way you conceptualize the world around you.

Many of the tools I've listed here are digital, and most of them cost money, which is a privilege that might not be accessible for you. All of this can be done with simple paper and pen; just start playing with exploring your ideas. Most importantly, read books and blogs, watch videos, follow the people who you find interesting and who are doing the work you're doing. Copy what they do to learn and find your own approach - then do that consistently over time.

Reiteration

Creativity is never a purely linear process. Each step will generate new ideas and insights that deserve to be refined and explored. Take the time to capture, evaluate and prototype them. It's easier to stick with the status quo because big ideas take time and energy to refine and build. The innovation process depends on you moving forward on an idea as if you know it's going to work and being okay when it doesn't. You have to be okay with failure, so fear doesn't get in your way from the beginning.

A few years ago, I started to hear people say, "man, stuff just tends to work out for you"! At the time, I would think...you know, you're right stuff does seem to work out for me it's fantastic - and it is fantastic. However, the work I put into my life to that point was lost in those statements. From the outside, that's probably what it seemed like. From my angle, I've been willing to put the work in when others suggested I do otherwise. The outcome is always the product of focused effort. Having and refining your ideas doesn't have to be random. Find the tools that resonate with you and start to apply them intentionally.

Luck is the residue of design. - Wesley Branch Rickey, Brooklyn Dodgers General Manager, 1946

Know your values

In Design Makes the World, Scott Berkun talks about the difference between building and designing, which I think is critical. Building is the process of making something that wasn't already there; design is improving something for someone. "...just because you built something the right way doesn't mean you built the right thing." This struck a chord with me because I've always felt the intention behind what you're doing more important than the act itself. For example, many people were planning to go to medical school as undergraduates. There's a collection of activities that are pretty standard on applications to medical school. Among them were volunteering at a hospital, leading student interest groups, and volunteering on service-learning projects in other countries. For each individual, they felt accomplished by having done these activities. Still, to a committee reading applications, they were a dime-a-dozen. Anyone could build their application to fit what they thought it "should" look like. Far more important is the narrative of why they did what they did and what they learned; how it changed them as a person and eventual physician. It was a design problem; what were they hoping to improve, and who were they doing it for? That was the critical piece.

Why? Why are you doing this? Your answer will serve as the roadmap while you tackle challenges, deal with setbacks and navigate the losses that will happen. The cycle of showing your work, receiving feedback, and reiterating requires an understanding of the whys that put it all into context - it provides a higher meaning.

There was an old Japanese carpenter who had worked his entire life striving to be the finest craftsman possible. After decades of working to build for other people, he decided it was time to retire to focus on his family. His boss, sad to see him leave, asked for one last favor; to build one more home. Kota reluctantly said yes. Frustrated that he would have to postpone his family vacation, Kota decided to just get the job done. He cut corners where possible and delegated the work to others as much as possible, finishing the house early. It was all up to code, but just so.

Now that it was finished, he finally had the blessing to retire. At his retirement party, his boss approached him with one last thing, the keys to the new house. Kota didn't realize he was building his own home; he forgot about the process through his frustration.

Parable from Chop Wood Carry Water

No matter your current situation, each day is only an opportunity to be who you want to be. It may seem like you are building for others, but really you are designing for yourself.

I hope you've taken something valuable from this series of posts. Honestly, I made these as a way to help clarify what all of this meant to me. I'm currently creating a new position with our emergency department that focuses on design in medicine and the process of crafting these articles has given me clarity on what it all means and how I think I'll be able to contribute to the world.

Make things you think others will value, get feedback, do it all again.

Cheers.

- Jordan