How to be anti-disciplinary [integration]

Use new experiences to compare and contrast old to create a unique perspective. You create value for others by integrating what you do and see.

![How to be anti-disciplinary [integration]](/content/images/size/w1200/2021/09/5B09787A-F79B-4DC6-A753-7BDF3E8BE609.PNG)

In the last post, I shared a brief overview of the path that led me to unlock what I understood was possible.

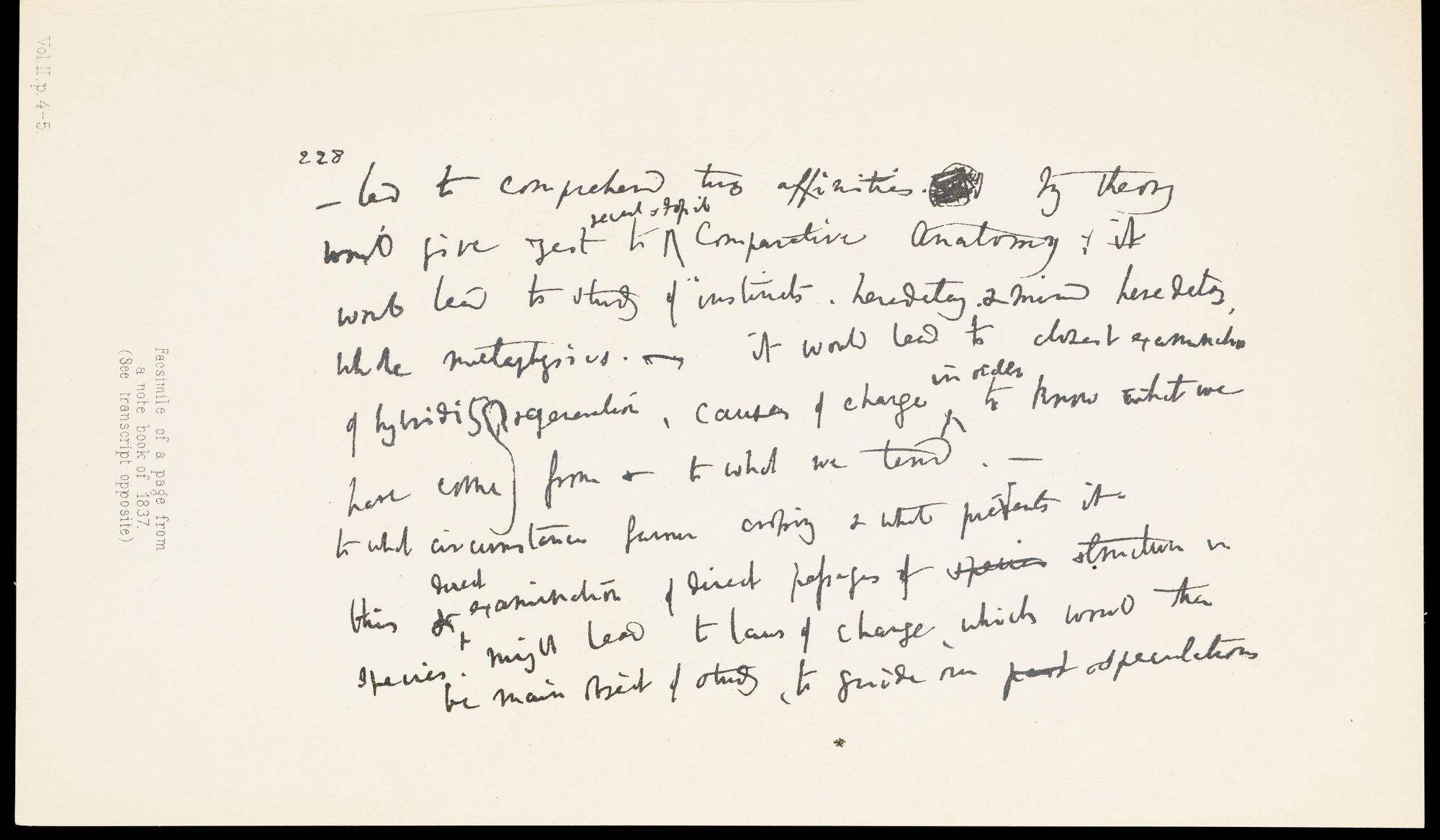

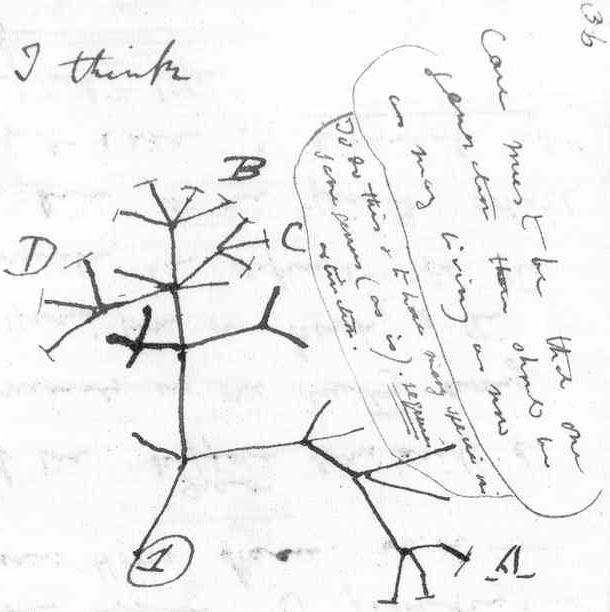

I've always been drawn to the classic portraits of scientists. The caricatures and legends of their day-to-day lives. The stories of people like Newton and Benjamin Franklin toiling in their home laboratories. Darwin was keeping pages of journals that chronicled his evolving understanding of the natural world. Edisons' notes and diagrams stashed away in tomes of notebooks. Early neurobiological research pioneers would build lab equipment collections in their homes, slicing and staining specimens in their basements - or bedrooms! There's a certain renaissance quality to those stories. They each eventually became icons in a particular domain but were never labeled as a "biologist" or "chemist" or "engineer" along until years into their careers. Instead, they just were individuals curious about the world around them. I love the idea of them allowing their curiosities to guide their work rather than an expectation of what they should do or be.

Break the Silo, Do Something New

That's the point of art - presenting an idea in a way that opens another person's understanding of the idea being shared.

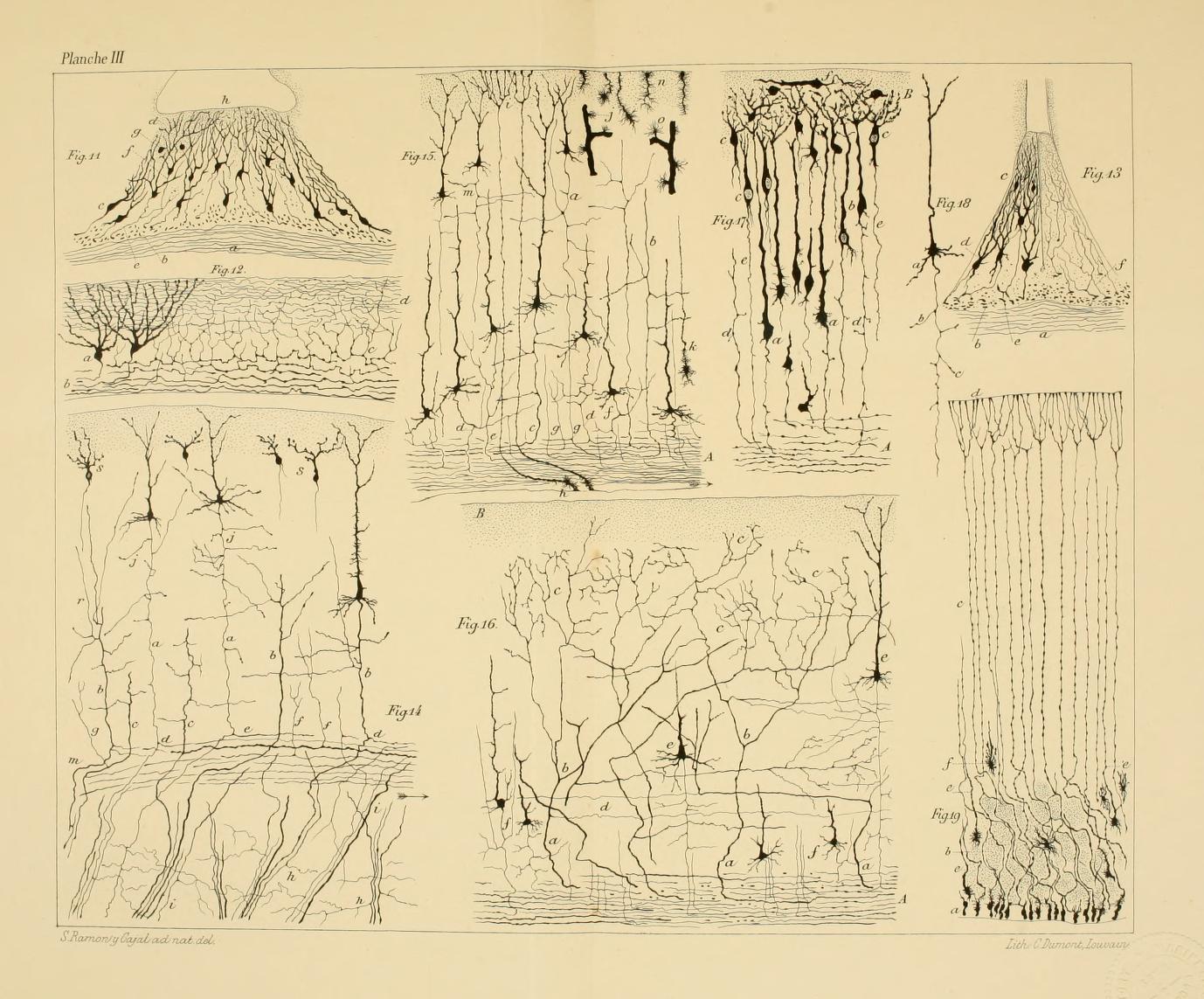

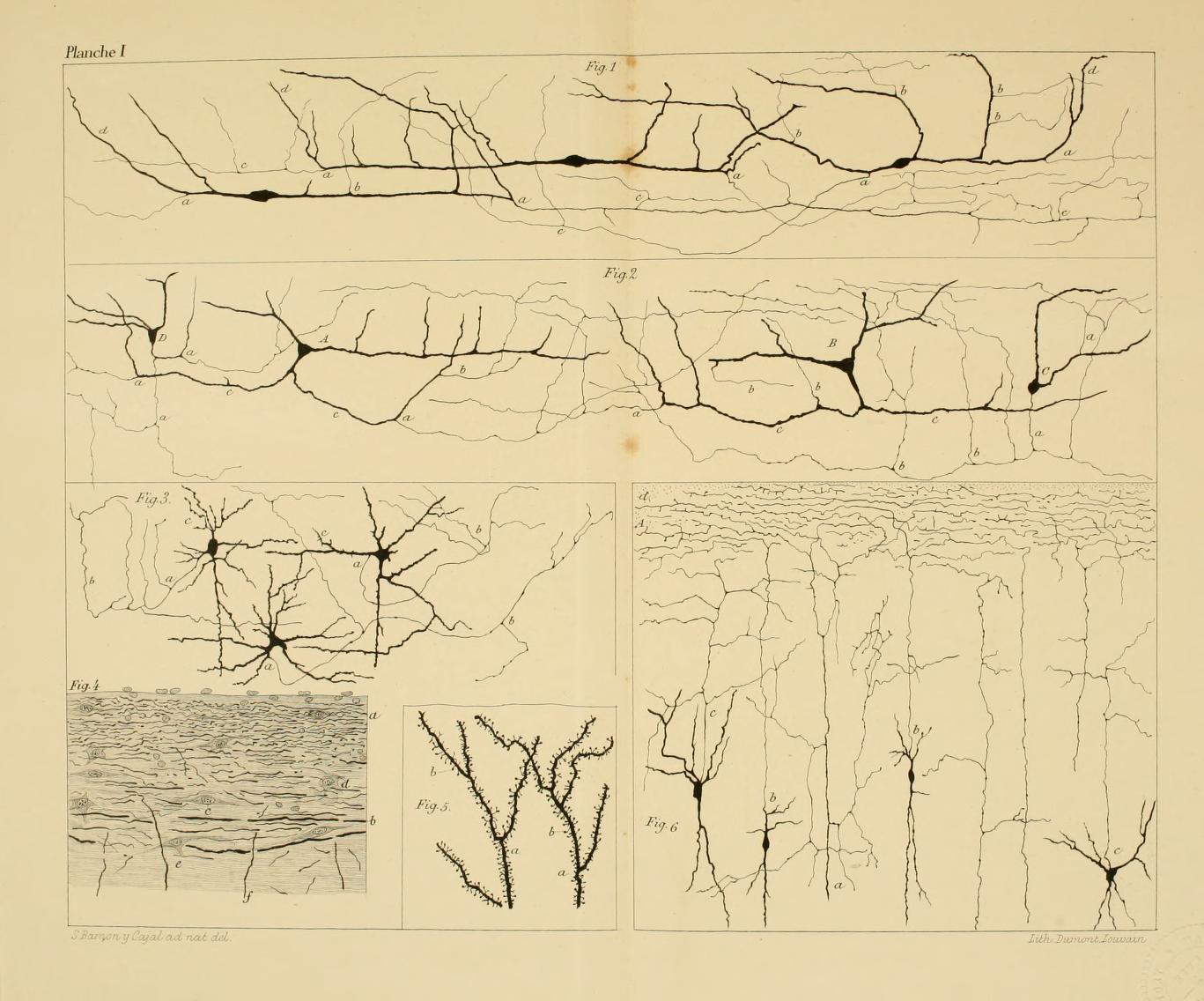

Ramon y Cajal is the epitome of art intersecting science. The Spanish neurobiologist was best known for his study of the histology of the human central nervous system. He created a lab in a spare bedroom where he would painstakingly slice, stain, and study tissue samples from the brain and spinal cords. He produced sketches and illustrations of what he observed, which have become regarded as some of the most important works of art in human history, ultimately leading to him winning a Nobel prize in the early 1900s. The illustrations Cajal created to map the architecture of the human nervous system fundamentally changed the way we understood the form and function of the brain. His interpretation and reproduction of axons and dendrites using paper and ink unlocked how others viewed the world. That's the point of art - presenting an idea in a way that opens another person's understanding of the idea being shared.

The best art cuts across domains, making something entirely new. Banksy doesn't just illustrate compelling images of people or things; they use illustrations in a way no one has ever seen to bring awareness to complex social topics and alter human behavior. Kanye doesn't just make hip-hop songs, he builds stories using fashion, physical textures, and sonic structure in ways no one else tries to create entirely new worlds. Tinker Hatfield doesn't just design shoes; he incorporates thoughts, emotions, and principles into sneakers to make some of the most iconic footwear the world has ever seen. Oslo didn't just practice medicine; he used prose to teach and inspire generations of physicians.

Using Passion to Unlock Purpose

I've been fortunate enough to discover what I'm passionate about by seeking, learning, and struggling through things that I found through my own process of discovery. It's led me to collect experiences in many areas and, along the way, do what I can to find a common thread between them. I was gifted the opportunity to dabble, fail and restart. I could try stuff on in a low-cost way. When you embark on a journey no one imagines you will complete, you're free of any expectations that would otherwise come with the process.

As I turned toward a career in medicine, I started to explore what medicine was. I really hadn't ever known a physician; sure, I went to the doctor when I was growing up, but I had never had a personal relationship with anyone in medicine. As my life carried me to the University of Wisconsin-Madison, I started volunteering in a local emergency department to see what it was all about. The pace and excitement were engrossing. I wanted to be closer to the action, so I took an EMT course over the following summer and cared for people on campus during the nights and weekends. In lectures at the university, I learned what study actually meant. I was pushed to truly dive into the material to understand scientific concepts and began to see the world around me entirely differently. It was disorienting and a bit of shell-shock, but I found my balance and began to excel.

You'll Never Get What You Don't Ask For

You can have all the confidence in the world, but to be successful, you need to collect data that says, "you're on the right path."

During my first year at UW-Madison, a couple of students shared an announcement at the start of a lecture about a service-learning project in Central America. I went home that evening and started to think about it more. I had wanted to do something that year to open my life to the world around me. I had friends planning study-abroad years and realized that had never been something on my radar and wanted to change that. I had no idea how I would pay for it; it didn't matter though I told myself I'd figure it out. Just do it. I was working at a local car dealership at the time, Zimbrick Honda. I asked the General Manager if he would meet with me after we closed one day and gave a 15-minute pitch about why the car dealership should pay for me to go on the trip. It was a scholarly project and would be a way for them to help me out. I proposed various ways to "show" the car dealership helping people and me in Central America.

I was half shocked when he said he'd pay for the trip in full with no strings; he just wanted to help me out. I don't think it registered with me at the time, but that gesture had a massive effect on my life. It was one in a series of events where I was told, "I believe in you." You can have all the confidence in the world, but to be successful, you need to collect data that says, "you're on the right path." If you blindly beat the same drum without incorporating feedback from the world around you, you won't get anywhere. The GM at Zimbrick showed me I was worth the investment. What I was striving for wasn't off base. It gave me the confidence to keep pursuing wild ideas.

I wanted to make the most of my experience in Nicaragua, so I set the intention that I'd completely immerse myself in the lives of the people around me. It was a short two weeks, but it put two things in motion that have become the core of who I am. The first was meeting Kyira, another student on the trip who has since become my wife. The second was a conceptualization of health as both a human right and a product of systems that either produce or stifle health. It was less a complete introduction to this idea and more an uncovering of what seemed to be how I intrinsically viewed the world. Like all worthwhile experiences, those two weeks created more questions in my mind than answers (not about Kyira, though - I had never been more certain of anything in my life. When my sister picked me up at the bus stop when I got home, the first thing I said was, "you need to meet this girl Kyira; I'm going to marry her someday.") I started to wonder how policies in the U.S. changed people's lives abroad. What role do I have in helping people live healthfully in other areas across the world? The following spring, I enrolled in the Global Health undergraduate program.

Integrating New and Old Experience

I'm not sure if it's been by mostly luck or if I had some intuition along the way, but every time I've pulled on a thread of interest, it's been woven amongst all of the other threads I've unraveled to create an intermeshed quilt of experience and life lessons.

Imagine this; I transferred to UW-Madison and started volunteering in the emergency department which led me to EMT school to work directly with patients. Meanwhile, I spent time in Central America which developed my interest in global and public health and eventually I'm was awarded a fellowship for a project I developed teaching CPR to physicians in El Salvador and eventually completed a Master of Public Health during medical school. I earned a degree in neurobiology which cemented my interest in the brain and the mind. With the help of my good friend Josh Landowski, we made a digital short story as a capstone for my MPH degree which planted creativity, media, and content creation directly in the heart of how I intend to approach the rest of my career. Then medical school confirmed the emergency department is the place I need to base my work in medicine. Everything I had done to that point showed me that medicine and public health intersected at the bedside in the emergency department. I knew emergency medicine was the field I could produce the greatest good for the world - I just wasn't entirely sure why that was, yet.

I'm not sure if it's been by mostly luck or if I had some intuition along the way, but every time I've pulled on a thread of interest, it's been woven amongst all of the other threads I've unraveled to create an intermeshed quilt of experience and life lessons. Whatever the reason, I feel fortunate to have worked out the way it all has. I realize now that that is the entire point; as you pursue your purpose, you have to dissect what you do along the way to discover what to carry with you. Your passions help propel you on a day-to-day basis to push through when things feel challenging. Your purpose is the reason you even get out of bed, to begin with. So what's my purpose then?

It's anti-disciplinary. I realize now that my purpose in medicine, in this world, is to help produce good for others by integrating knowledge across domains. I understand the world from a place that sees problems as a collection of issues that aren't siloed to one space. A patient having a heart attack has had years of behaviors that have accumulated and contributed to the heart disease that's now causing the problem. Patients who struggle to keep their medicines straight aren't likely "non-compliant" but likely can't keep the prescription schedule straight - it's a design problem. This seems obvious on the surface, but looking at problems through this lens often gets missed.

Next time, I'll walk you through the epiphany I had when I stumbled across the idea of anti-disciplinary work and how I think it can help you do more of what's meaningful in your life.