Lessons Learned While Becoming an Emergency Physician

The path to achieving anything worthwhile is challenging. Looking back on my path to becoming an emergency physician, I've learned a few lessons that I think can be applied to any part of life.

In 2008 I made the decision that I would embark on a journey to become a physician. No one else in my family had gone to college. This past week was the last week of my training in emergency medicine. This is not the end, per se, but rather the culmination point. I've accumulated 13 years of studying, learning, practicing, and reflecting to reach a point of competency that allows random strangers to trust me with their life.

I knew residency would be challenging, though I didn't expect to do it during a once a century pandemic, historic wildfires, ice storms, heat domes, and social unrest.

Here's a summary of what I've learned the past few years as an emergency medicine resident.

We all make it up as we go

There seems to be a universal experience in life when our parents and the adults around us, who seemed infallible when we were children begin to show signs of imperfection later in life. You realize that people who you thought had the answers, sometimes don't. Becoming a parent within the past couple of years myself, I notice the moments when I'm not sure what to do or say but take my best guess. I saw the same evolution happen during the past three years as an emergency medicine resident. We rely on the help of others around us because we simply don't know how or what to do in all cases. When I started down this pathway, I understood the limits of emergency medicine, but not always the limits of those around us.

See, when you're forced to be the one making a call, the imperfections of your understanding are put out in the open for other people to see. "I don't know" is a challenging thing to say in medicine. We train to be the ones to know. Not knowing isn't a failure, though. Not knowing what to do next is.

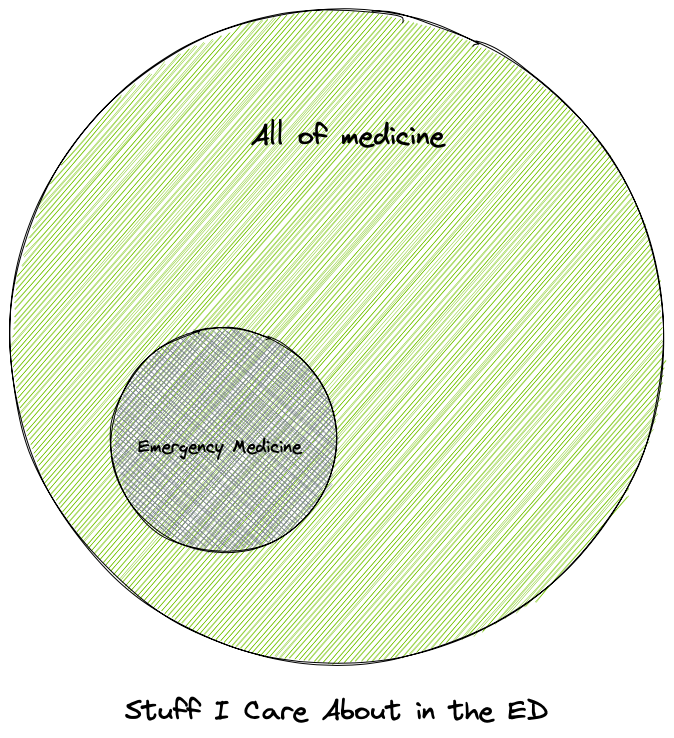

In the emergency department, my job is to not lose. I play by a certain set of rules and a defined list of things I can't miss. Whether it's a serious infection, a subtle heart attack, or a child being neglected, there is a definitive list of things I need to be keenly tuned into. I try to find the other stuff too - stuff that won't kill you - but sometimes I don't...or can't..because of the constraints of my job. That doesn't mean my job is done though, I need to know where to turn next or where to send the patient.

When you don't know something, you need to know who to ask.

Life is a complex place. We're continually running into things we've never seen or done. It's okay to not always be the expert. A core skill in life and the emergency department is to know the art of asking for help. You haven't failed until you've allowed your pride or ego to impede you from taking the next step to lean on someone else. The antidotes to a lack of understanding are honestly and vulnerability.

The challenging thing about medical training is the pressure to know the answer. The path to becoming a doctor is paved with test questions. While in medical school, the primary way of "testing" your knowledge in the hospital is to ask you questions in front of everybody else. When done well, the gaps in your knowledge are uncovered and filled in. The more typical thing is for your gaps to be uncovered and the shame of not knowing to drive you away from the opportunity of learning. Instead of learning about a disease process you become a master at learning body language and saying the right words, at the right time.

This spills into residency training. While the performative aspects aren't as important in residency, most young doctors have developed such deeply ingrained habits it's difficult to adjust. "I don't know" remains a challenging phrase for physicians to use. I've learned to embrace the limited time and information I'm forced to function in. I've found the relationships I've formed within the health care system are most effective when I have an awareness of what I'm not allowed to miss and being vulnerable with those around me.

- When giving sign out to my colleagues for a patient I'm admitting, being honest about not fully knowing what's going on but clear with what I'm worried about.

- When I talk to consultants, being clear about what I need from them and communicating the boundaries of what I know or can do.

- With patients when I feel like they are safe to go home but clear that I don't yet know what's wrong but think there is more work to be done.

When you feel like you're the only one who has no idea what's going on, stop and look around you. Everyone else is simply making it up as they go to.

You need to have a system in place to understand the rules of the game you're playing, know what you're not allowed to get wrong, seek help when needed and be honest and vulnerable.

Mean people are usually scared or insecure

Residency is hard work. Like really hard work.

Residents are paid around $60,000 per year to work 60-100 hour work weeks, regardless of how many patients they take care of. Every time I call another resident to either consult for or admit a patient, I'm adding to their workload. I'd guess 90% of the people who graduate medical school are great people who sought medicine to help people and make a difference in the world. Despite the best intentions and altruism, it's challenging to maintain compassion and empathy.

Not infrequently, I've had other doctors question my medical knowledge, berate me for calling them and "wasting their time", and flat out refuse to help me. Early in training, I wasn't sure what to think of those interactions. Naturally, it was upsetting and would make me feel angry. "Who are they to treat me like that?!” I’d think to myself. What I was missing at the time though was an understanding that that other person was using a defense mechanism to protect themselves from whatever it was that's scaring them. Most of the time it's a tool of persuasion to try and reduce their workload. Occasionally it's to try and make up for their own lack of understanding or insight into the situation. It might go something like this:

- The new consulting fellow minimizes a patients' presentation in a subtle way to steer the encounter away from an intervention. They're overwhelmed and fighting the imposter syndrome that sets in when transitioning to a new role with more responsibility and the expectation that you know.

- The overwhelmed admitting resident on overnight questions the need for admission. The additional admission adds to their already long list and they're afraid of missing something.

- You're criticized for making a mistake that "they would never have made". The other person has likely made a similar mistake in the past but is now "showing" how smart they are by putting you on the island - you are alone among the incompetence - to convince themselves that they are now competent because they wouldn't do what you just did.

In a field that asks people to sacrifice years - decades - of time, commit to thousands of hours of study, tests that are multiple days long, days of work that last 24, 28, or more hours straight, I have a hard time thinking my colleagues are anything but good people. There are surely exceptions to the rules, but the vast majority of people in medicine are good people who sometimes are overcome by fear or insecurities and develop habits and behaviors to defend against them. Those habits are honed in medical school and refined in residency.

This translates to every other area of life. More often than not, people operate from a place of fear. Fear of failure, fear of being broke, fear of discomfort. People develop defenses that look like substance use, procrastination, anxiety, dependence on others, etc. to deal with fear and insecurity. Take road rage as an example, when someone cuts you off, it's so easy to be pissed - "how could they do that?!" What we all fail to recognize is that traffic doesn't happen to us - we are traffic! When you can start to shift your thinking and recognize the interconnectedness of life, you can start to appreciate that other driver didn't wake up this morning to cut you off (most likely). They're just trying their best to get through their day and you happened to be the one affected by it.

You'll never be ready

Once you start to understand that no one truly has it figured out, you realize that means you'll never actually be ready - for anything. There's never a good time to have a kid, start a business, learn a new skill, quit smoking, work out, etc. There's only now. To be an artist, all you need to do is create. It's simple but not easy. The thing that makes it challenging to start is the struggle of not being good at the start. It's hard to build the habit when the first few dozen, or hundred, attempts just aren't good.

Residency training is exactly that - you go to work every day at the start knowing what feels like next to nothing. It feels that way because every day you're forced to make decisions about something you've never experienced before. Slowly, as you accumulate experiences, you build confidence and refine your medical knowledge. At the end of three years, I'm definitely not an expert yet, but I've developed a baseline competency and more importantly have developed a system for gathering, assimilating, and refining skills and knowledge.

To be a writer, all you need to do is put words down on paper or screen. To be a photographer; make photos. To be good, to be a professional, you have to do it every day, regardless of how you feel. A physician is a professional because they do the work, every day, whether they want to or not. If you want to be a thing, start being the thing, every day and be open to feedback. As you do it over and over, you'll learn, adjust and improve. After a few years, you'll be competent and keenly understand what you need to become great.

The challenging thing about a medical residency is that it's just tiring. It's a huge volume of work, making hundreds of high-stakes decisions each day, for relatively low pay, in a field that at times can feel thankless. If you don't fully commit to the process it will begin to erode your edges and you won't get from it what you need. You can't be one foot in and one foot out in residency, you have to be 100% in. That doesn't mean residency has to be 100% of your life, but it means you need to show up to lectures ready to improve. Each shift in the hospital needs to be seen as the most important part of your day. If you start to think about residency as an inconvenience or try to skate through it with a minimum effort, the frustrations (and there are plenty) of the experience will start to take a greater weight and skew your experience towards the negative.

Intention and persistence always beats talent

Be clear about what you're hoping to accomplish. You have to invest some time thinking about what success would look like for you. Once you have clarity in that, just show up regularly. Showing up is often the biggest differentiating factor between people who accomplish what they set out to accomplish and those who don't. That doesn't mean just physically being there though - you need to mentally be there. That goes back to committing 100%.

Talent is taken for granted. You don't have to hone talent - it's just there. Skill, though, requires constant sharpening. Skills erode without attention paid to them. The difference between talent and skill is that you struggle to build skill so you feel it more. You understand what it means because you know what it's like without it and know what it was like to get it. People always feel the pain of having something taken away from them more than the joy of being given something. That's why intention and persistence will always lead you somewhere way more meaningful than any talent you may have.

Decide where you want to go, show up every day, and lay the path, brick by brick.

Learn how to craft your narrative

One of the main components of any job interview is to tell the other person why they should pick you. It's no different getting into college, medical school, residency, or a job after residency. I've had to sit in dozens of interviews (on both sides), write personal statements every few years, and just learn to tell people what I'm all about. That meant I needed to be clear on that myself. I needed to understand who I truly was and where I was headed. It's a process that definitely takes a ton of work - but it's imperative to get to where you want to go.

Life is just a bunch of storytelling. We sell products to each other by telling stories about how our lives would change if we just bought this one thing. We teach one another by telling stories about how atoms interact with each other and how a fast heart rate in someone with shortness of breath should always make us think about pulmonary embolism. To do anything well you need to learn how to tell a good story.

Here's how I've learned to think about storytelling and building your own narrative:

Story structure

The classic is a three-part story built over an arc. Tension rises, the main character overcomes the series of great obstacles, then the character reflects on the journey as the tension falls. Think of your path in the same way. How did you decide to go down the path you did? What obstacles did you face? What'd you learn and how are you a better person because of it? Physically map your story to understand how the pieces fit together.

Each step provides insight for the next

Learn to extrapolate and find connections between seemingly unrelated things.

When I was a senior in high school I knew I wanted to go to college. I wasn't sure why, I just recognized it was a path to go to something bigger. The problem was I hadn't done any work to that point to learn what the process of college admissions was at the time. Obviously a bit late to the game. At the time I was in a computer animation course and was really enjoying it. I never considered myself an artist per se, but figured it was cool so that's what I'd do. As I started down that path I realized my true passion was science and biology and realized I wanted to go to medical school. As I've progressed in medicine, my interest in visual arts is still firmly rooted in my day-to-day life. It functions as a filter to enhance my knowledge and skills as a physician. In fact, it was through my interest in design that I came to realize that my training in public health was really a degree in designing healthy lives. I could see the overlap between how a software designer builds an app and how health policy is shaped. Understanding human behavior, telling good stories, working with empathy. As you build experiences and seek to tie new things together, you build a latticework of new ideas and innovation that helps you tell a more convincing story.

Reflect

All of this requires constant reflection. It's a challenging skill to develop in a world that rewards constant movement. "What are you doing after high school"? "After college?" "After medical school?" "After residency?" "Make sure to post regularly!" "Did you get my email?"

Carve out time to turn inwards. I've found meditation to be crucial - even if for just a few minutes every day. It has to be every day though. You have to stop the automatic, often subconscious automatic process that happens throughout the day. You have to change the relationship you have with your mind to observe your life and who you are without judgment. Otherwise, it's way too hard to see things as they actually are. You'll miss the unique things about your experience that make you who you are.

More than anything though, don't ever let someone tell you you can't do something. It will happen. Each step along the way I've had advisors try to nudge me down different paths. "You're thinking of going to college? A technical school or apprenticeship would be a great option for you." "I know you'd like to go to medical school, you should think about a plan B just in case." "I'm worried you aren't approaching medical school the right way." "Oh, you're interested in emergency medicine residency at OHSU? How about applying to these other programs too, just in case?"

Take good advice and leave the rest. The jobs of formal advisors - whether at a high school, university, job, or otherwise - are to serve the median. They can't commit the time and attention to the outliers because of the constraints of the job. If they tell you something isn't possible, but you are ready to put the work in to make it happen, move on to the next person who's willing to help you.

Know where you want to go, show up every day, reflect, and move forward.